ADA - places visited——互动展览设计

"The sculpture's name, Ada, references Ada Lovelace, who, in the 19th century, wrote a series of notes to Charles Babbage about his idea for an “analytical engine."

这件雕塑的名字叫艾达,是指艾达·洛夫莱斯,他在19世纪给查尔斯·巴贝奇写了一系列关于“分析引擎”的笔记

Some interactive, kinetic sculptures, like Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project or Roman Ondák’s Measuring the Universe, require the viewer to also help complete it. Others, like AnL Studio’s Lightwave, interact in order to take on anthropomorphic, animated qualities. Well, Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s Ada, an interactive sculpture (...) does both.

一些互动的、动态的雕塑,比如奥拉弗尔·埃利亚松(Olafur Eliasson)的天气项目或罗曼·翁达克(Roman Ondák)的《测量宇宙》(Measurement the Universe),也需要观众帮助完成。其他的,比如AnL Studio的光波,为了表现出拟人化、动画化的特性而进行交互。Karina Smigla Bobinski的Ada,一个互动雕塑(…)两者都有。

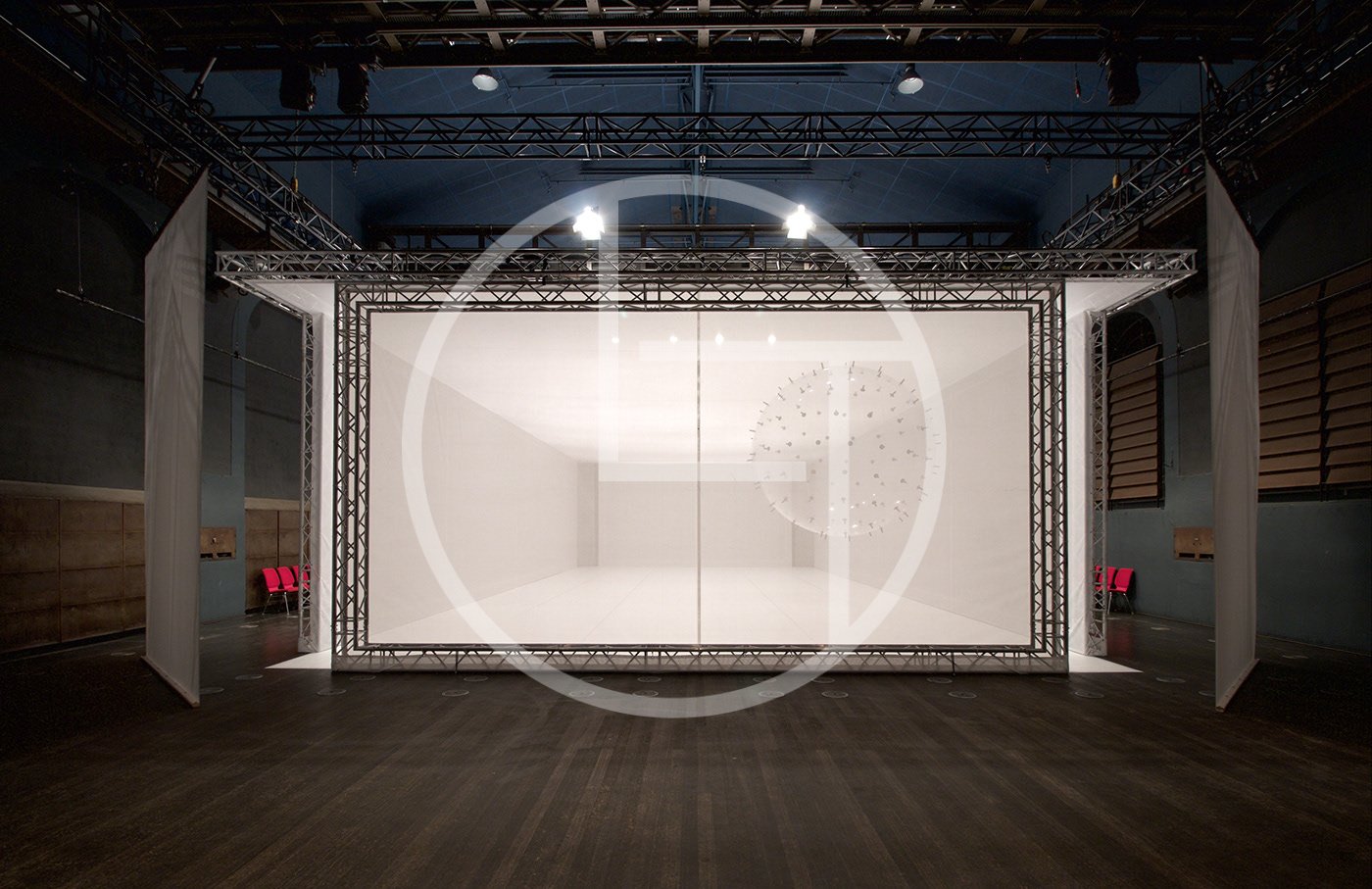

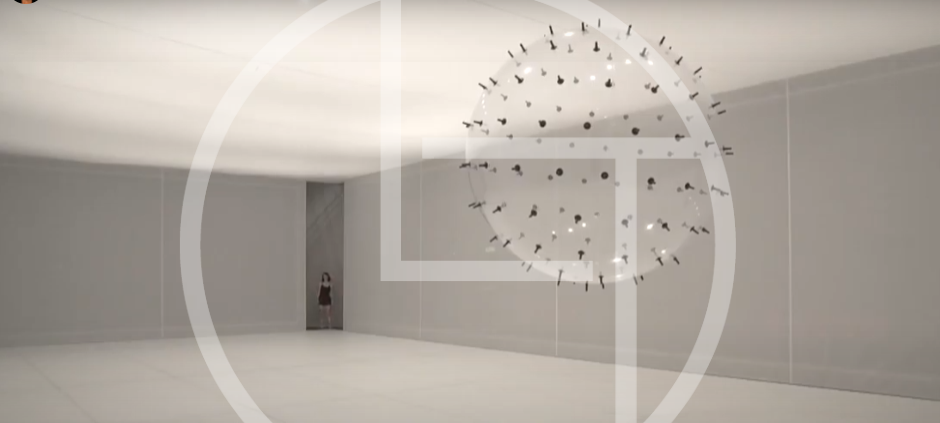

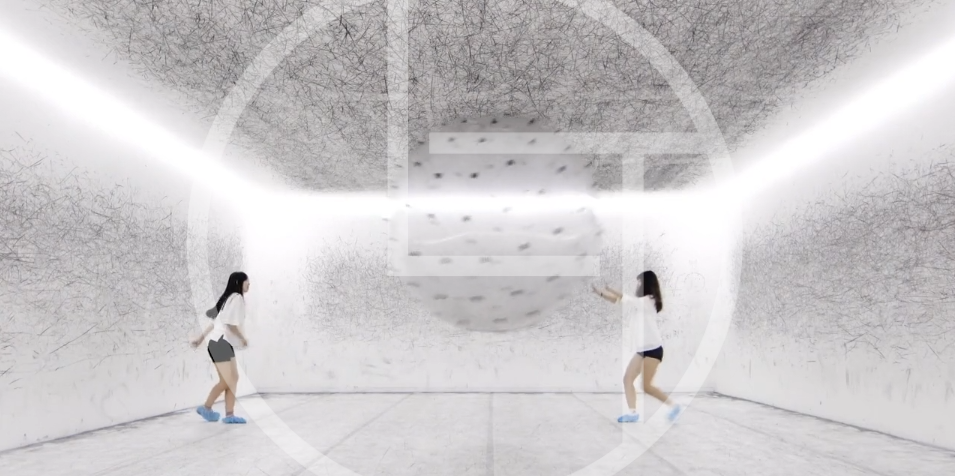

The Ada – analog interactive installation is a transparent helium balloon about three feet in diameter with 300 charcoal sticks stuck on the balloon, each about 10 inches apart, using a technique that Smigla-Bobinski developed especially for this artwork. What people do when they come into contact with the floating, membrane-looking spiked globe as it floats around the gallery space is where it gets interesting.

这个装置是一个直径约3英尺的透明氦气球,气球上粘着300根木炭棒,每根木炭棒相隔约10英寸,使用的是斯米格拉·博宾斯基(Smigla Bobinski)专门为这件艺术品开发的技术。当人们接触到漂浮在画廊空间中的、看起来像薄膜的带刺球体时,他们会做些什么,这才是有趣的地方。

Some people approach the orb gingerly; other times they grab the charcoal sticks like handles and try to bend it to their will. Some people bounce it around like a beach ball at a baseball game. About halfway through, an old man tries to actually draw something, only to have it wrestled away by the laws of physics. Every time it hits the wall, the charcoal scratches its mark along the walls, turning the alien-looking, transparent membrane into an automatic art-making machine. In this, the sculpture references her namesake, Ada Lovelace, who, in the 19th century, wrote a series of notes related to a paper on her friend Charles Babbage’s “analytical engine,” i.e., computer, which they hoped would also make works of art as well.

有些人小心翼翼地接近球体;有时,他们会像抓把手一样抓住木炭棒,并试图按自己的意愿弯曲木炭棒。有些人会像棒球比赛中的沙滩球一样弹起它。大约在画到一半的时候,一位老人试图画一些东西,结果却被物理定律夺走了。每次碰到墙壁,木炭都会沿着墙壁划伤它的痕迹,把这个看起来像外星人的透明薄膜变成一台自动艺术制作机器。在这件作品中,这座雕塑引用了与她同名的艾达·洛夫蕾斯(Ada Lovelace),她在19世纪写了一系列与她的朋友查尔斯·巴贝奇(Charles Babbage)的“分析引擎”(analytical engine,即计算机)相关的笔记,他们希望计算机也能制作艺术作品。

Smigla-Bobisnki hints that she's fine with not necessarily even knowing the extent of what she's created: “What here is exactly the work of art?" she wrote in an email to me. Ada? Or the drawing on the wall? ... Or both?” What she begins, the audience completes, and the result is an interesting look at the balance of power in what is essentially a rigged collaboration. “Once you set her into motion, she just works away,” Smigla-Bobinski continues. “The blacker she gets from the charcoal and the more she is handled by visitors, the more she seems to be some kind of alive. Even I, who built her, sometimes gets the illusion of her being a living thing.”

斯米格拉·波比辛基表示,她不必知道自己创作的作品的范围:“这艺术品到底是什么?”她在给我的电子邮件中写道。是艾达?还是墙上的画?……或者两者兼而有之?”她开始这个艺术,观众帮她完成,结果有趣的是看到了一种合作中的平衡。斯米格拉·博宾斯基继续说道:“一旦你让她动起来,她就会不停地工作。”。“她从木炭中得到的颜色越黑,被游客接触的次数越多,她似乎就越有活力。就连建造她的我,有时也会觉得她是个活物。”

浏览器自带分享功能也很好用哦~

浏览器自带分享功能也很好用哦~